This research paper was presented at the Open Air Cities Conference in Athens, March 2025 and has been published at the Sustainable Development, Culture, Traditions Journal (SDCT).

Abstract

Seemingly unending ecological disasters, floods and forest fires, along with ever-increasing social unrest continue to shed light towards the limits of growth — not only in Greece, but throughout the globe. In an effort to mend the relationship between human existence and planetary boundaries, the post-growth paradigm advocates for decoupling from economic indices as the sole determinant of prosperity. In terms of spatial planning it calls for ensuring a degree of regional sufficiency, investing directly in social services and infrastructure, proposing absolute limits to urbanization and prioritizing socio-ecological prosperity. Like many major transitions, however, this approach is mostly confined within academic circles or small-scale projects and is far from being institutionalized. This can be ascribed to several barriers, like limited societal acceptance, lack of alternative visions beyond growth-reliance or intense bureaucratic procedures. This paper argues that bioregionalism — the understanding of a territory through its ecological functions, geo-morphological and socio-cultural characteristics — is of utmost importance in operationalizing the post-growth agenda due to several synergistic qualities that allow for bypassing key barriers. For example, bioregionalism could enable the emergence of a territorial place-attachment, encourage transnational cooperation, as well as propose eco-social indices of prosperity against GDP. Particularly interesting for the realm of spatial planning, bioregionalism suggests a land-based approach to territorial management. Building on this idea, this paper speculates about an alternative system of territorial administration through bioregions. Responding to the pressing issues of lacking water management, these bioregions could be administrative entities that mirror the basins of major rivers in Greece. This idea is tested through a case study of the river Spercheios. Overall, such a system could empower local governance, especially in rural areas, negate paralyzing bureaucratic procedures, potentially engage disinterested citizens and allow for new spatial imaginaries to emerge.

Key words

Post-growth, Bioregionalism, Bioregion, Spatial Planning, Spatial Imaginary

Introduction

While Greece’s economic trajectory of the past years has been consistently praised for its “sustainable growth”, the ongoing social crises and ecological disasters shed light on a crucial disconnect. Conceptions of progress are usually based solely on economic indices, often ignoring social and ecological ones, or treating them as byproducts of economic advancement. This perception can skew decision-making towards short-term economic gain rather than aiming for long-term ecosocial prosperity. Such an economic-growth-reliant way of thinking can be particularly problematic for spatial planning, especially considering our rapidly changing climate reality. Greece’s unpreparedness in these fields is clearly evident — from the destructive flooding of the Thessaly region or the ever-repeating urban floods that have ascended to the realm of the “norm”, to the immense wildfire in the region of Evros and all around Greece, to the painful Tempi instance that brought to light both lacking infrastructure management and political corruption. We cannot continue business as usual — a different paradigm is required.

This paper explores post-growth as such a paradigm, an approach for achieving social, ecological and spatial justice and prosperity. It is examined through the perspective of a spatial planner — and not an economist — with the intention of furthering its operational agenda and suggesting ideas to other planners and institutions in Greece and beyond. It is largely based on the research conducted and its findings of my Master Thesis titled Another Rural (Xanthopoulos, 2024), in which I investigated a distant-future spatial imaginary for a rural bioregion in Greece. There, drawing from literature, I argued for the connection of bioregionalism with post-growth planning. In this paper I further this argument. First, I will briefly explore the definition of the post-growth paradigm and bioregionalism, while emphasizing their relevance for the case of Greece. Second, the multi-faceted barriers of operationalising a post-growth planning paradigm will be explored, while highlighting the potential of a bioregional approach to bypass them. Third, exploring lessons learned from my previous research, I will envision a bioregional administration for Greece and argue for this approach’s capability to allow for a post-growth planning to emerge. Finally, I will reflect on the approach’s potential shortcomings, as well as point to further research.

Defining the terms: post-growth (planning) and bioregionalism

Endless economic growth is impossible on a finite planet

As the most recognizable quote of post-growth advocates suggests, the post-growth approach challenges the hegemonic notion of an ever-growing economy, imagined as being decoupled from planetary bounds. Instead, this paradigm advocates for a “voluntary, democratically negotiated, equitable downscaling of societies’ physical throughput until it reaches a sustainable steady-state” (Büchs and Koch, 2019, p. 155). There is some confusion about the terminology, because it is often used interchangeably as degrowth. As Savini (2023) puts it simply: post-growth is an approach, a “useful concept to stimulate discussion”, but that in itself lacks tools; while degrowth is an agenda, it does “one step more” towards a politicised approach by demanding “socio-ecological redistribution” (p. 5). More recently, Savini refers to degrowth as an “ideology in the making” (Savini, 2025). For the purpose of this paper, I will continue using the more general post-growth approach. Regardless, this term emerged as degrowth in the nineteen-seventies through the term décroissance by André Gorz, a French political ecologist (Kaika et al., 2023, p. 1194). It was at the same year as the publication of the 1972 “Limits to Growth” report, which highlighted the impossibility of perpetual population and economic growth, utilising the first examples of computer simulation. The report urged immediate research on our economic model but those concerns were constrained mostly within academic circles. Since then much has changed and the impacts of such a growth-centric thinking are more evident, extensively studied and communicated than ever.

Post-growth as a “project of transitioning systematically toward a new society” (Savini, 2021, p. 1077) proposes an overwhelming agenda of societal, political and institutional changes. Items of this agenda include, among others, reduction of working time, a universal basic income and establishing a cooperative and regenerative economy (Büchs and Koch, 2019, p. 160). According to Strunz and Schindler (2018) a post-growth society would be characterized by three key conditions: a material throughput that aligns with ecological limits, phasing away from GDP-driven decision-making and directing gains in resource and energy productivity towards reducing material throughput — until the first condition is met (p. 70). As it is hard to envision such changes from an abstract, economic viewpoint, philosopher Kate Soper (2020) explores what a post-growth lifestyle would entail, advocating for a redefinition of what constitutes the “good life” itself; against overconsumption, closer to nature, more free time and less work. However, she highlights that such pleas “will remain theoretical in the absence of the powers and pressures required to translate them into effective practice — which means attention must also be paid to the possible agents and processes of transformation” (Soper, p. 162). Soper insists that furthering the post-growth approach would require emphasizing the benefits of a post-growth lifestyle instead of only debunking pro-growth thinking, in order to combat the negative connotations that arise from a perceived absence of societal growth.

The post-growth paradigm is an attempt to halt the hegemony of pro-growth thinking, which also still persists in academic circles. Most pro-growth scholars, policy-makers or commentators often dismiss post-growth approaches as a utopia or a dream — even during the presentations of this conference. However, much evidence illustrates that reaching our climate goals with our current strategies might actually be the impossible dream. Among other researchers, Vogel and Hickel (2023) clearly outline that “the decoupling rates achieved in high-income countries are inadequate for meeting the climate and equity commitments of the Paris Agreement and cannot legitimately be considered green”. Calling for a more holistic approach, they propose that we will need to “pursue post-growth demand-reduction strategies, reorienting the economy towards sufficiency, equity, and human wellbeing, while also accelerating technological change and efficiency improvements” (Vogel and Hickel, 2023). Thus, post-growth thinking critiques “green growth” or “sustainable growth” as scholars acknowledge the inability of these approaches to actually lead to meaningful change.

A planning paradigm

In order to both envision and enact such a post-growth paradigm, examining the role of spatial planning is imperative — a topic that many scholars are investigating. First, it is important to recognise that our current planning paradigm “has bound itself into a pro-growth agenda that is mentally and institutionally hard to overcome” (Durrant et al., 2023, p. 288). Instead of facilitating social and ecological prosperity, the role of planning processes has regressed into the facilitation of development and economic growth, in order to meet policy goals through their benefits. To this end, Federico Savini (2021) explores a spatial planning paradigm of urban degrowth by critiquing three growth-reliant mechanisms and proposing three degrowth counter-paradigms. These are: (a) from functional polycentrism to polycentric autonomism, or proposing radical cooperation instead of competition between regions, (b) from scarcity to finity, or halting the forces of land development through stricter regulations, and (c) from euclidean zoning to habitability, or empowering local governance and emphasizing the relationships between human and non-human agents (Savini, 2021). In short, post-growth planning would greatly differ from the functions, goals and tools of the current paradigm. Instead of targeting and facilitating a vague advancement measured through abstract economic indices, it would require direct investment to social and ecological prosperity.

This is very relevant for the case of Greece. Over the past century, growth in Greece has become interlinked with tourism, and spatial planning processes have taken on the role of facilitating tourism-driven development in both urban and rural settings. Such a pro-growth planning is evident in both national and regional levels and is best exemplified through the recently published “Special Framework for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development for Tourism” or “Ειδικό Πλαίσιο Χωροταξικού Σχεδιασμού και Αειφόρου Ανάπτυξης για τον Τουρισμό”, in which all Greek regions, with minor exceptions of few hyper-touristic areas, are regarded as territories for potential “development through tourism”. This deep-rooted approach fosters competition between regions, or even municipalities and neighborhoods, and reduces the notion of place into mere destination, rather than promoting cooperation and long-term ecosocial prosperity. It has resulted in the gradual abandonment or degradation of other economic activities that were intrinsically tied to the land, like crafting or agriculture. Thus, it is imperative to examine alternate ways of enacting spatial planning, beyond purely economic, short-sighted goals and to reckon with our rapidly changing climate reality.

A bioregional lens

Rarely cited within post-growth literature is the concept of bioregionalism. It refers to the acknowledgement “that we not only live in cities, towns, villages or ‘the countryside’; we also live in watersheds, ecosystems, and eco-regions” (Wahl, 2018) and aims to achieve “a co-adaptive fit between local cultures and local environments” (Evanoff, 2017, p. 57). In this way, bioregionalism can be understood as a critique on anthropocentric understandings of place and their subsequent delineations, advocating for a place-based approach (both geomorphological and social) to a region’s definition. Bioregionalism imagines vastly different decision-making processes, where “power would flow not from the global to the local, but from the local to the global” (Evanoff, 2017, p. 60). A bioregional paradigm of territorial management would entail decision-making taking place at the “smallest possible level while still permitting cooperative action at larger scales when necessary, particularly through confederal institutions” (Evanoff, 2017, p. 61-62). While it can be argued that humans have always operated through such principles — living through and at the land — the concept of contemporary bioregionalism is traced to the nineteen-twenties and has metastasized to various other ideas over the last century (Duží and Fanfani, 2019, p. 7). This could be understood as a response to how our contemporary lifestyles have become alienated from natural processes, particularly in urban areas. A plea to adopt a more nature-centric lifestyle and view is not controversial; what is more contested through is the definition of the bioregion itself and whether such place-based delineations are more appropriate in responding to our climate goals, in both policy and administration. In this paper I argue that bioregionalism is of utmost importance in operationalizing the post-growth agenda due to several synergistic qualities or opportunities that allow for bypassing key barriers of the post-growth transition. These are explored below.

Exploring barriers of post-growth transition and the opportunities offered through bioregionalism

Despite considerable thought and continuous effort from post-growth scholars and advocates, the post-growth paradigm has remained confined within academic circles and found spatial manifestations only with small-scale initiatives. Few cities in Europe have embraced these ideas by utilising the analytical framework offered by Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economy and embracing a model of circular economy (for a brief exploration of terminology see Savini, 2023), while the majority still operate within a pro-growth model — Greece being one of them, as there have been little to no actions towards meaningful change with contemporary urban planning. To this end, Kaika, Varvarousis, Demaria and March (Kaika et al., 2023) sketch out five ideas for operationalising degrowth beyond its currently limited approach and application. These include to (a) emphasize the importance of historical literacy when engaging with degrowth ideas, (b) not evade engaging with planning institutions to formalise degrowth through policy and practices, (c) research further on how degrowth initiatives could be scaled up successfully, (d) highlight the relevance of spatial thinkers and (e) to address more explicitly issues of race, class, gender and labour when discussing the dependencies between Global North and Global South in degrowth thinking. Similarly, Savini (2025) pleads for the contestation of existing institutions that perpetuate extractivist, land-degrading and unjust pro-growth ideologies and to propose new institutions to “shape socio-ecological practices” (p. 2, p. 17). However, in order to further contribute to the operationalisation of the post-growth approach, it is important to examine why it has thus far received little response within contemporary urban planning. This can be attributed to a number of multi-faceted barriers, from operational, institutional or politico-economic dimensions. These barriers are explored by drawing from relevant post-growth literature, placing importance in the ones most relevant for spatial planning and relating to the case of Greece. At each barrier, the synergistic quality or opportunity presented by a bioregional approach will be explored. For a summary of barriers and opportunities, see the table below.

Table: Barriers of the post-growth transition and opportunities offered through bioregionalism.

| dimension | barrier to post-growth transition | opportunities of bioregionalism |

|---|---|---|

| operational | planetary agenda | site-specificity |

| limited societal acceptance | territorial place-attachment | |

| individual network reliance | regional cooperation | |

| institutional | lack of spatial visions | bioregional imaginary |

| bureaucracy | redefinition of administrative boundaries | |

| politico-economic | unemployment | investment in relevant sectors |

| alternatives to GDP | bioregional indices | |

| pension schemes | resource-sharing and caring | |

| political polarisation | land-based approach | |

| public debt | non-economic performance |

From a planetary post-growth agenda to a network of site-specific agendas

The first inherent barrier to operationalising the post-growth approach is the nature of its scope. As was examined before, it proposes an overwhelming agenda of ambitious societal, political and institutional changes in a planetary scale. It is challenging for planners and policy-makers to translate these planetary ideas to local actions. This is especially relevant for countries like Greece, that suffer from poor territorial management and are oftentimes unable to translate EU-level policies to the regional or municipal level. To this end, as explained by Savini (2023), the Doughnut Economy analytical framework is utilised as a tool for post-growth planning, allowing for a process of mapping overshooting sectors and identifying ones that are underperforming, e.g. Greece’s energy overshoot and underperforming social services. With the regional as the ideal scale for doing so, this approach recognises that there is indeed a need to understand the site-specific metabolic flows, both material and immaterial, as well as interdependencies between regions. Of course, as Kaika et. al. (2023) highlight, the dynamics between Global North and Global South should be considered in this process as well (p. 1204).

Such a process of analysing the region through a post-growth lens would be hindered by anthropocentric delineations of space, as they would fail to consider the continuity and complexity of natural and human systems. In this way, post-growth planning could benefit from bioregionalism, as a deeply local, place-based approach could allow for the bottom-up emergence of a network of spatial post-growth agendas that are both contextually relevant for the territory at stake — rather than generic, designed for an abstract regional entity — and democratically negotiated.

From limited societal acceptance to territorial place-attachment

Another inherent barrier of any major transition is the limited societal acceptance — especially for the post-growth one as it requires ambitious changes in many levels; personal lifestyle, political, institutional etc. Limited acceptance of these ideas can be observed from multiple actors: scholars themselves, citizens, policy-makers, planners and governments. As an emergent ideology within academia, most of its rhetoric utilises economic terminology and scholarly language that is often hard for the general public to understand. Beyond the linguistics of post-growth and despite growth being a “fairly recent phenomenon which only picked up in the 19th century together with the industrialisation of Western economies” (Büchs and Koch, 2019, p. 160), the hegemony of growth-centric thinking today permeates people’s identities and life goals, shaped “by ideas of social progress, personal status and success through careers, rising income and consumption” (Büchs and Koch, 2019, p. 160) and remains “rooted in everyday imaginaries as the only solutions” (Kaika et al., 2023, p. 1205). Despite also the many recurring environmental catastrophes — like the flooding of the Thessaly region and wildfire of Evros in 2023 — and the numerous human and non-human lives claimed, citizens and policymakers have not yet questioned “the imaginary of growth as a panacea for a better life” (Kaika et al., 2023, p. 1205). This growth dependency is also evident in governmental visions (exemplified through Greece’s energy overshoot, see Xanthopoulos, 2024, p. 74-77) and unfortunately planners themselves, as pointed out by Lamker and Schulze Dieckhoff (2022). In this way, pro-growth planning is disallowing climate adaptation measures and transitioning to self-sufficiency against an extractivist economy.

Despite this, an attachment to place, history and culture persits, even though it might usually be expressed on an individual level, rather than a collective one. Bioregionalism presents an opportunity to unite these fragmented attachments into a shared territorial consciousness — a territorial place-attachment — by linking local identity, knowledge and ambitions with bottom-up governance. Such an approach emphasises the shared risks and opportunities of living in the same territory and in this way could transform passive sentiments into active force, specifically with ecological preservation in mind. The concept of place-framing is relevant here, as analysed by Feola et al. (2023) in regards to sustainability transitions. It refers to an “exercise through which collective memories and future visions are connected and are co-constituted through collective processes of the socially constructed framings of place” (p. 3). A bioregional approach to post-growth planning could highlight the importance of understanding people’s existing connections to land and utilising them for the cultivation of ecocentric values necessary for the post-growth transition to be catalysed.

From reliance to individual network to bioregional cooperation

Despite its theoretical advancements, post-growth thinking has yet to be manifested physically or spatially in significant scales, aside from small-scale initiatives. These usually include “worker-owned and managed businesses” (Büchs and Koch, 2019, p. 160) or “cohousing, farmer’s markets, self-sufficient housing, non-commercial sharing, and urban gardening” (Savini, 2021, p. 1077). Such initiatives often rely on individual networks to be established and operate, and demand substantial investment of personal time and involvement. With the absence of formal support from institutions, they struggle to be up-scaled and gain permanence. On the contrary, they often face significant trouble securing land as well as political and economic resistance, as seen in the case of Amsterdam’s Lutkemeerpolder, in which grassroots urban farming efforts have been halted for decades due to market-driven policies (Savini, 2025). More broadly, such efforts remain dependent on “a relatively small, geographically dispersed, and highly intellectually diverse research community” , limiting their capacity to influence policy and public opinion (Crownshaw et al., 2019, p. 118). Any post-growth project imagined is inherently land-dependent, deeming it vulnerable to speculation from real-estate-driven policy shifts and market pressures.

Bioregionalism could offer an alternative framework to help overcome these challenges, by rooting them within ecological and territorial structures — bioregions with decision-making power — rather than individual networks. A bioregional approach to territorial planning emphasizes the importance of decentralized, community-led decision-making, which would in turn shift from the reliance of individual efforts towards collective, place-based strategies. In this way, by embedding post-growth initiatives within a bioregional framework would become more resilient against market pressures and policy obstacles, bringing together diverse stakeholders required for such a major shift: farmers, cooperatives, municipalities, policy-makers, citizens.

From a lack of spatial visions to bioregional imaginaries

Now examining institutional barriers, perhaps the most important one would be the absence of spatial visions in planning — a barrier also linked with limited societal acceptance. While there is a great deal of thought about the role of post-growth planning in “debunking” or exemplifying the structural dependencies of growth and their spatial manifestations, there has been less emphasis on how an alternate planning paradigm would actually operate in practice. Post-growth planning is inherently future-oriented, as it proposes ambitious shifts and emphasizes long-term goals like ecological restoration, establishing resilient economies and networks of care. As Kaika et. al. (2023) illustrate, “degrowth can provide an alternative imaginary for the future” so long as it is translated into “spatial images, plans and practices for it to start having significant impact and effect” (p. 1205). Yet, in many contexts spatial planning remains short-sighted, driven by immediate profit and failing to critically engage with the future. Institutional inertia and “the embeddedness of the growth-based capitalistic economic system in these co-evolved institutions and ways of thinking makes it difficult to transition to a degrowth system”, “defuturizing” planning by constraining the openness of future possibilities and reinforcing path dependencies (Büchs and Koch, 2019, p. 160). This is particularly relevant for countries like Greece, where spatial planning has lacked long-term planning and has a tendency to degrade or outright cancel spatial visions — even since the state’s founding with the alteration of the 1833 Kleanthis and Schaubert plan for Athens. This growth-oriented mindset detaches ecological concerns from planning and desplaces them to the realm of activism, benefiting from loosely defined regulations, lack of transparency and community participation. It has only recently been that the large-scale development in Ellinikon might show a shift towards intentional spatial planning, albeit still within a growth-driven framework. However, it does, in a sense, show an important moment in history for planning to critically engage with spatial visions, as in the absence of deliberate efforts to craft and perform post-growth imaginaries, the dominant, implicit vision of growth — primarily expressed through tourism—will continue to prevail.

National-scale visions are almost always bound to economic performance of GDP and usually fail to consider the intricacies and pluralities of place; thus are more susceptible to growth-oriented strategies. On the contrary, a bioregional approach to spatial planning would entail crafting critical, place-based visions by addressing contextual manifestations of growth and understanding local concerns, visions and ambitions, histories and knowledge — a bioregional imaginary. Through this, post-growth planning would be able to become spatially articulated, more relevant and engaging, to contest the hegemony of growth and to influence public opinion. Aligning with pleas for “prefigurative planning”, this approach could address the growing “sense of loss of the future” by “performing the future in the present” (Davoudi, 2023, p. 2278).

From bureaucracy to bioregional administration

Bureaucracy is an often overlooked institutional barrier of the post-growth transition, despite being a fundamental hindrance. Post-growth planning would prioritise societal and ecological concerns and demand an immediate response to the urgencies of the changing climate, yet lengthy administrative procedures and fragmented governance structures would seriously obstruct such measures and actions. This bureaucratic inertia is incredibly prevalent in Greece, but also among many other countries in the EU and beyond. Lengthy procedures actively contribute to the “defuturizing” mentioned in the previous barrier. Again to contextualize this struggle in Greece, a striking example is the prolonged delay in updating the national climate crisis plan. The one currently in place was published in 2008, based on research from 2006 which utilised data from 2000. Efforts to draw up the new version started only in 2020 and for almost five years now have been stalled in governmental procedures due to repeated micro-adjustments (Lialios, 2023). This highlights a severe lag in policy implementation, which does not align with the demands of post-growth planning for swift actions.

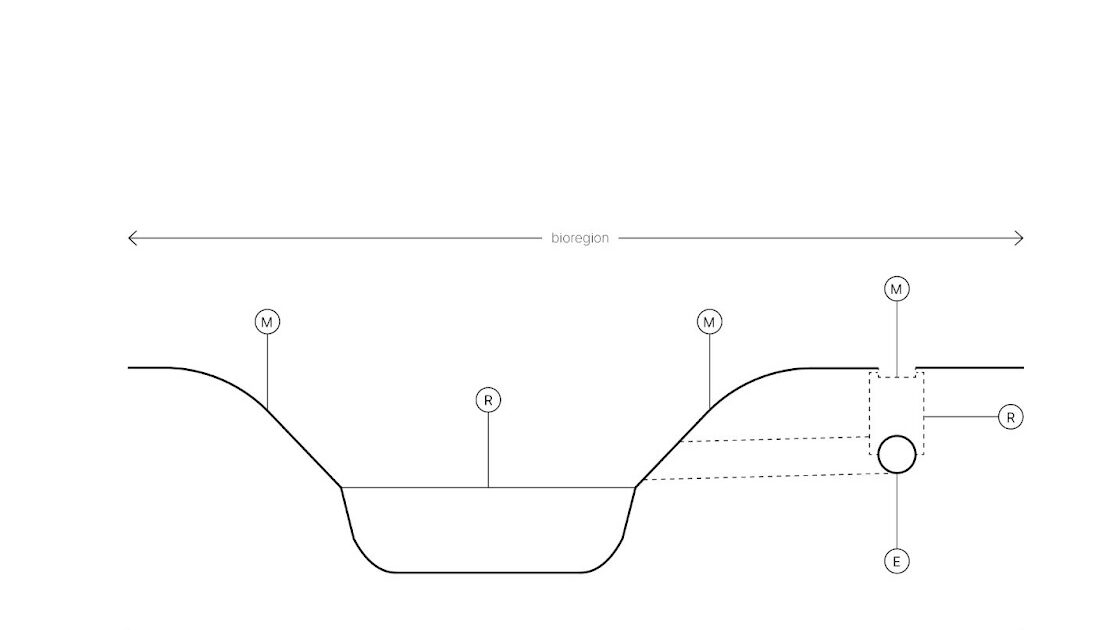

Bioregionalism advocates for a decentralization of administration, doing away with governance structures that are slow and disconnected from local issues, and suggests enacting decision-making at the scale of the territory-at-stake and through its natural systems in mind. This could assist in overcoming such bureaucratic hurdles, bridging contextual needs and relevant actionable policies. To illustrate this point, a common Greek anecdote regarding water management can be utilised: “The example of manholes on the national road network is well known. The municipality has to clean the grate, the Periphery the barrel, and the Water Supply & Sewerage Company (EYDAP) the actual pipelines. This problem is even more difficult in cleaning the river streams. The Periphery has jurisdiction over the river bed, the municipality over the river slopes. These are things that at some point we will have to regulate holistically” (Dandogloy, 2023). Instead of this fragmented decision-making scheme, a bioregional administration would consolidate responsibilities under a single (bio)regional entity, empowering local actors and allowing for responsiveness and flexibility in implementing post-growth policies (visualised at the diagram below).

Diagram: Diagrammatic section of river and water administration. The decision-making power is distributed among many administrative bodies, causing confusion and inefficiency. A bioregional approach would unite this fragmented administration into a single decision-making entity.

M: Municipality, R: Region (Perifereia), E: EYDAP (Water Supply & Sewerage Company)

Politico-economic barriers

Various politico-economic barriers pose significant challenges in advancing the post-growth (planning) approach, as identified by Strunz and Schindler (2018), however bioregionalism could not address them explicitly and thus they will only be briefly examined, as they also do not pertain directly to the realm of spatial planning. First, the most pressing of them is unemployment, as economic growth is seen as indispensable for the creation and upkeep of employment opportunities, thus instilling fear about the loss of jobs. This may hold some merit, since a post-growth society would consciously transition away from certain types of employment that currently dominate western imaginaries — what David Graeber refers to “bullshit jobs”; mundane, corporate, unfulfilling and detached (see the ideas on reduction of work of Kate Soper, 2020). In a post-growth society, labor ought to be shifted to low productivity sectors, like nursing or public employment (Strunz and Schindler, 2018, p. 72). In a similar vein, bioregionalism emphasizes the need to care for the land and highlight the importance of increasing employment in agriculture, as well as environmental protection and restoration or the craft sector. Second, a major barrier is the dominance of GDP as the index of prosperity. Despite its widely recognised and studied failures to account for environmental and social well-being, there has been little effort to transition towards other measures. A bioregional approach could introduce localized indices that focus on environmental protection, resource use and social welfare. This would also be more tangible and more easily measurable on a (bio)regional scale, rather than the often misleading national level. If integrated with EU funding mechanisms for rural development could provide meaningful incentives towards a post-growth transition. Third, Strunz and Schindler (2018) highlight pension schemes as a significant barrier, as they “rely on economic growth to offset demographic change” (p. 73). When considering the many reductions to pensions in Europe — and particularly in Greece due to the austerity measures — politically supporting ideas about a post-growth economy would be unpalatable towards older voters. However, related to the barrier of unemployment, a post-growth society seen through a bioregional lens would allocate much more employment towards the elderly, potentially providing more meaningful, personal care towards the rising ageing population than growth-driven economies could through monetary means.

Political polarisation and debt are two other significant politico-economic barriers to the post-growth transition, especially for Greece. Political polarisation disallows garnering the necessary electoral support for ambitious and radical post-growth ideas. Soper suggests that a post-growth program would benefit from alliances between Labour and Green parties (Soper, 2020, p. 164) as a way to bridge this divide. Bioregionalism may stem from anarchist ideas, however in its essence is a matter-of-fact approach, calling attention to the pressing yet practical issues at hand, like floods or wildfires. In this way, unlike traditional political platforms, bioregionalism inspires cooperation by emphasizing the ecological and morphological characteristics of a region. Debt on the other hand represents a structural impediment for post-growth policies, as it prevents the implementation of alternate measures of progress that differ from economic growth. This of course rings very true for Greece. The need to achieve growth through GDP overshadows ecological and societal concerns, thus bioregionalism here does not suffice in offering direct solutions. However, it could provide a framework to ground economic prosperity within a bioregional scale, in which other forms of labour and performance could be best coupled with post-growth policies.

An exploration of bioregional administration for post-growth planning

The examination of barriers and opportunities has illustrated the synergies between post-growth planning and bioregionalism: Overall, bioregionalism could translate planetary-scopal post-growth ideas to tangible, contextual agendas, ground decision-making to local realities, foster collective engagement, enhance scalability of post-growth initiatives and advocate for flexible, decentralized governance structures. What is deemed most important is that bioregionalism suggests a conceptual, operational and regulatory framework required for establishing a post-growth planning paradigm. Thus, it could aid in operationalizing a sustainable, just and resilient transition, decoupled from and beyond growth. Now, moving from theory to design experimentation, in this segment I will briefly explore how these ideas could be spatially and institutionally manifested by utilising a case-study of a Greek bioregion that was developed in the context of my thesis Another Rural (See Xanthopoulos, 2024).

Defining the bioregion

Greece “remains one of the least decentralized administrative systems of the EU with local government” (Nikitas and Vasilopoulou, 2022, p. 5, Sotiropoulos, 2018, p. 393) — which when coupled with its dependency to pro-growth national politics, would make adaptation of post-growth policies incredibly challenging. There have been efforts to counteract this, like the merging of municipalities through the Kallikratis scheme in 2011, in order to create larger “economies of scale, decrease local government expenditure and establish local government units sizeable enough to marshal resources and skills useful for the absorption of EU funding” (Sotiropoulos, 2018, p. 396). However, any such effort has hitherto proven unsuccessful. Steering away from this dysfunctional system, the definition of the bioregion was firstly explored by looking towards non-anthropocentric, nature-based delineations: floristic regions, freshwater ecoregions, protected zones and climate zones (Xanthopoulos, 2024, p. 64 – 67). This brief literature exploration failed to reveal a suitable spatial framework for the application of post-growth planning. Instead, looking towards the pressing issues of lacking water management in Greece and the history of bioregionalism in the nineteen-seventies (Duží and Fanfani, 2019, p. 9), the watershed is chosen as the way forward. Rivers defy anthropocentric borders and administrative perceptions, and demand a holistic planning approach. In this experiment, the watersheds of the major rivers within the Greek territory are imagined as entities with administrative, decision-making power. This could be the result of joining small-sized municipalities, while allocating decision-making power from the administrative regions (περιφέρειες), as well as public-sector employees. For some cases, the existing administrative, municipal boundaries are not unlike the watershed territorial limits, making this transition easier to imagine bureaucratically. In a more extreme version, municipalities and regions would no longer be required. While this approach might seem overambitious for the Greek context, it is in some ways reminiscent of the Dutch Rijkswaterstaat, which holds much more administrative power than municipalities or regions in relation to water management — thus not entirely out of touch. Also, it highlights the importance of international cooperation, as river ecosystems span neighbouring Balkan countries. While this may be contextually relevant for Greece, it is not proposed as the panacea for imagining a bioregional administration system for post-growth planning — limitations of this approach will be explored in the end. Overall, such an approach could allow for post-growth policies and a planning paradigm to enact them by localising decision-making, bypassing paralyzing bureaucratic procedures and gaining public acceptance by targeting territorial issues, like floods and forest fires, that are in the public perception more than ever.

Understanding the bioregion through a post-growth lens

From these imagined bioregional administrative units, the watershed of the river Spercheios is chosen as a case-study. It is a predominantly rural region located in central Greece, currently governed through two small municipalities — Makrakomi and Lamia. Geomorphologically, it is a valley surrounded by the mountains of Oiti, Timfirstos and Othrys, from which many streams feed into the main river, flowing to the Malian Gulf. The region faces complex issues of intense rural abandonment, frequent destructive flooding and dealing with an aging population, while agriculture remains the dominant occupation. Despite the region being used for food production for several millennia, it is only during our contemporary era of growth that human activities have disturbed the natural environment to this extent, and consequently our human habitats as well. The intensification of agriculture has resulted in immense loss of forest cover (which is crucial for flood prevention and ecosystem services), along with the vernacular agroforestry knowledge and techniques. Pro-growth planning contributed to this through short-sighted infrastructural projects, like the construction of a linear diverter, poorly-planned transportation networks and the expansion of agricultural land on the river territory and coastal marshland. At the same time, while the region is untouristic, growth-through-tourism remains deeply embedded in people’s perceptions of the future (often imagined through the revival of hot-spring tourism), even though most have little hope and trust in institutions.

Exemplified through the research framework explored here, a bioregional approach to post-growth planning assisted in the formation of contextual post-growth agenda by demanding a historicized approach in tracing spatial manifestations of growth and understanding the site-specific embeddedness of growth-thinking in public perception. Instead of solely focusing on critiquing the current planning practices or advocating for short-term goals and visions, a bioregional post-growth planning paradigm would allow us to focus on long-term and ambitious shifts, informed by local issues, visions and knowledge. Further research could entail how such a process would be formulated as an analytical tool for post-growth planning.

Constructing a post-growth bioregional imaginary

With an understanding of contextual problems and ambitions, formulated into a contextual agenda, the role of post-growth planning would be translating it to policies and local actions. However, a bioregional approach to post-growth planning would first engage with the construction of spatial imaginaries that are capable of counteracting the underlying yet dominant growth-based ones, emphasising the future-oriented role of planning. Foresight methods from the field of future studies could be utilised for this task, in order to envision these post-growth futures — something that has hitherto not been extensively researched. To visualize and democratically debate these future-oriented spatial imaginaries an alternative tooling approach might be required. Traditional planning media and processes would likely not suffice in doing so; their shortcomings are evident: they are often exclusionary, abstract and unclear, especially for contexts like Greece, where familiarity with drawings, masterplans and lengthy technical reports is limited from the general public. Instead, a bioregional post-growth planning approach could utilize storytelling, co-visioning and participatory methods, in order to construct tangible, engaging and critical plans. For example, Another Rural (Xanthopoulos, 2024, p. 142-195) entailed a narrative-based exploration of such a speculative distant post-growth future within the context of a rural bioregion, imagined through a combination of fiction and academic writing. This was conducted from a first-person perspective, by imagining a day in the life of a bioregional dweller, exploring ideas of employment, housing, ecosystem restoration, decision-making, from a multitude of scales; from the individual house to the role of the EU. Such a speculative and creative process of bioregional visioning could be pivotal for post-growth planning, by engaging disinterested citizens and allowing for future-jumps beyond typical, generic, disengaging visions of the future.

The next step is to move from such long-term visions to place-based, local actions — or for these far-away-future spatial imaginaries to be performed in the present. This could entail engaging with tactical design interventions, focusing on key-projects that would catalyse a post-growth transition through relevant policy implementation. For example, such a design project of Another Rural was the revival of traditional “περαταριές”, or make-shift wooden structures used to safely transport cargo or animals from one side of the river to the other up until the twentieth century. These were re-imagined as automated, seasonal connecting paths, coupled with water data collection technology, in order to provide seasonal access to the riparian zone and enhance connectivity within the valley, without resorting to large-scale, costly infrastructure that historically has not stood the tests of frequent flooding. Such a key-project bridges ancestral knowledge, vernacular techniques and lifestyles with new technologies and contemporary planning. This aligns with post-growth ideas of utilizing ancestral knowledge and vernacular techniques, questioning pro-growth infrastructural projects of transportation, proposing instead low-cost, nature-based solutions. Thus, instead of aiming for the application of abstract post-growth policies, a bioregional approach to post-growth planning could explore a network of catalytic projects to spatially translate them into actions.

Reflections and Conclusions

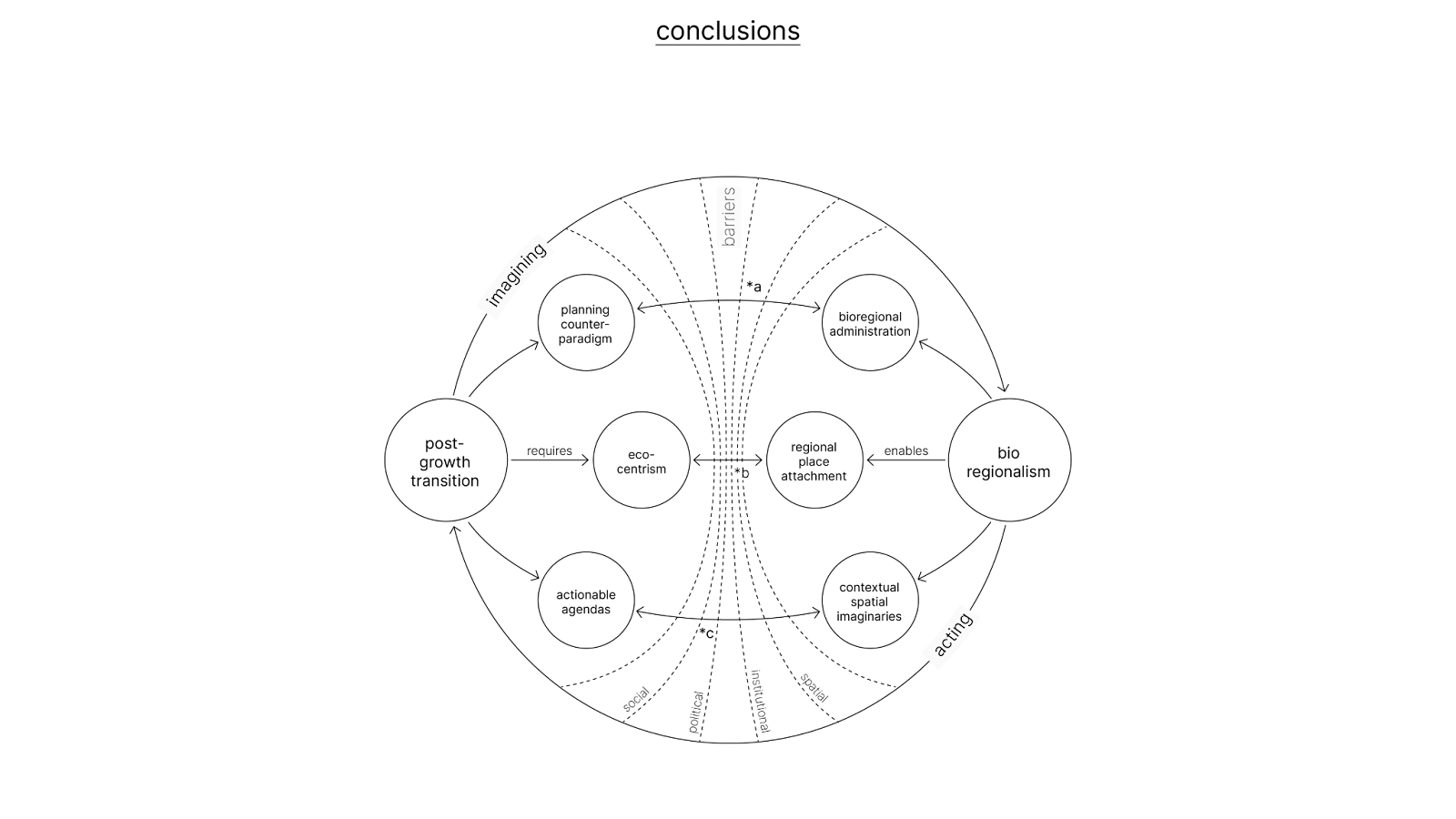

This paper has attempted to illustrate that operationalising post-growth thinking would require more than just EU- or national-scale policies or small-scale experiments — it would require a spatial planning counter-paradigm, a deep ecocentrism and the formation of actionable agendas. However, current efforts remain limited as they face numerous barriers across operational, institutional and politico-economic dimensions. Bioregionalism emerges as a compelling framework to overcome these obstacles by fostering a bioregional administration paradigm, by enabling regional place-attachment and by shaping contextual spatial imaginaries. These synergistic relations could allow for a process of imagining post-growth futures and providing pathways to enact them through spatial planning.

However, certain pitfalls must be acknowledged in this approach. First, a bioregional approach to post-growth planning would rely on a high number of experts present: skilled planners, ecological and water management experts, as well as governance specialists. Aside from many countries like Greece currently lacking this capacity, there is a risk of technocracy if planning processes become overly dependent on such specialized knowledge. To circumvent this, bioregional post-growth planning should emphasize local knowledge and community participation, ensuring that expertise serves the community rather than alienating it, while still maintaining a critical position within a global context. Second, the emphasis placed in local, sustainable, land-based lifestyles could lead to unwanted fetishization of rural life. A bioregional post-growth planning ought to engage critically with the often harsh realities and structural challenges of rural living—not romanticizing the past but balancing historical awareness with an action- and future-oriented perspective. Third, a high degree of regional autonomy could lead to isolation or exclusionary tendencies, and thus to co-optation. Especially when we consider the rise of far-right politics around the globe, forming resilient trans-regional networks should be sacrosanct. These would enable exchange of knowledge and resource-sharing, fostering cooperation and communication. The above points are summarized in the diagram below, illustrating the conceptual framework proposed by a bioregional approach to post-growth planning.

Diagram: The synergistic qualities between the post-growth planning approach and bioregionalism allows for a process of imagining alternative ways of living and acting upon them – however this approach has its potential pitfalls and limitations.

a: technocracy, b: rural fetishization, c: co-optation

Looking towards the experimentation of this approach, few limitations need to be pointed out. The example of bioregional administration through watersheds that has been explored is mostly relevant for Greece’s mainland, where territorial continuity allows for administrative restructuring. This approach emphasises Greece’s agricultural heritage in order to distance itself from tourism-driven planning, however, in doing so it does not consider the many islands. These function as distinct bioregions with unique dynamics and given their embeddedness to Greece’s growth-centric tourism economy and the many challenges they face today due to hyper-tourism, a different approach ought to be explored. Finally, looking ahead, further research is needed in investigating the role of spatial imaginaries for post-growth planning. This could entail comparative work through experimentation with diverse case studies throughout Europe, exploring both rural and urban regions, in order to understand how territorial visions could shape societal transitions away from growth-oriented paradigms. Further work is also required in exemplifying bioregionalism as a transformative planning approach, not only in envisioning post-growth futures, but also in bringing them into being.

References

Büchs, M., & Koch, M. (2019). Challenges for the degrowth transition: The debate about wellbeing. Futures, 105, 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.09.002

Dandogloy, N. (2023, October 3). OTA: Όλες οι αλλαγές στην Αυτοδιοίκηση. Οικονομικός Ταχυδρόμος, (In Greek) retrieved from https://www.ot.gr/2023/10/03/epikairothta/ota-oles-oi-allages-stin-aytodioikisi/

Durrant, D., Lamker, C., & Rydin, Y. (2023). The Potential of Post-Growth Planning: Re-Tooling the Planning Profession for Moving beyond Growth. Planning Theory & Practice, 24(2), 287–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2023.2198876

Duží, B., & Fanfani, D. (2019). Urban bioregion concept: From theoretical roots to development of an operational framework in the European context.

Evanoff, R. (2017). Bioregionalism: A Brief Introduction and Overview. Aoyama Journal of International Politics, Economics and Communication, No. 99, 55–65.

Feola, G., Goodman, M. K., Suzunaga, J., & Soler, J. (2023). Collective memories, place-framing and the politics of imaginary futures in sustainability transitions and transformation. Geoforum, 138, 103668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.103668

Kaika, M., Varvarousis, A., Demaria, F., & March, H. (2023). Urbanizing degrowth: Five steps towards a Radical Spatial Degrowth Agenda for planning in the face of climate emergency. Urban Studies, 60(7), 1191–1211. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231162234

Lialios, G. (2023, November 6). Ενέργεια: Ο νέος χάρτης για τις ΑΠΕ. Η ΚΑΘΗΜΕΡΙΝΗ. https://www.kathimerini.gr/society/562710001/energeia-o-neos-chartis-gia-tis-ape/

Nikitas, V., & Vasilopoulou, V. (2022). Public administration reforms in Greece during the economic adjustment programmes. [Discussion Paper 167]. European Commission. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2765/996401

Savini, F. (2021). Towards an urban degrowth: Habitability, finity and polycentric autonomism. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(5), 1076–1095. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20981391

Savini, F. (2023). Post-Growth, Degrowth, the Doughnut, and Circular Economy: A Short Guide for Policymakers. Journal of City Climate Policy and Economy. https://doi.org/10.3138/jccpe-2023-0004

Savini, F. (2025). Degrowth as ideology: Making values for the soil of Amsterdam. Environmental Values, 09632719251318139. https://doi.org/10.1177/09632719251318139

Soper, K. (2020). Post-Growth Living—For an Alternative Hedonism. Verso Books. https://www.versobooks.com/en-gb/products/929-post-growth-living

Sotiropoulos, D. (2018). Public administration characteristics and performance in EU28: Greece. European Commission. Directorate General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/297733

Strunz, S., & Schindler, H. (2018). Identifying Barriers Toward a Post-growth Economy – A Political Economy View. Ecological Economics, 153, 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.06.017

Vogel, J., & Hickel, J. (2023). Is green growth happening? An empirical analysis of achieved versus Paris-compliant CO2–GDP decoupling in high-income countries. The Lancet Planetary Health, 7(9), e759–e769. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(23)00174-2

Wahl, D. C. (2017, August 15). Bioregionalism—Living with a Sense of Place at the Appropriate Scale for Self-reliance. Age of Awareness. https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/bioregionalism-living-with-a-sense-of-place-at-the-appropriate-scale-for-self-reliance-a8c9027ab85d

Xanthopoulos, G. (2024). Another Rural: a post-growth imaginary for rural Greece. Master Thesis. Technical University of Delft, Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, https://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:9d589a99-dd0d-45d4-9cfb-6c9119bf584f